So much has happened in the last 17 months. I was musing with a friend the other day that it feels as if we have lost a year of our lives. In some ways we have. And, in my neck of the woods, thankfully things are pretty much back to the way they were before COVID-19 took over everything.

All our small-town happenings have returned. We had our annual 4th of July town celebration, music on the square starts back up this week, Sunday afternoon Brews-and-Tunes has returned to the story telling plaza, the story telling festival is scheduled to happen this October and we will be performing Spot-on-the-Hill live this year. It is wonderful.

But there is much that has happened in the lives of many in our communities, related to the pandemic, that will have a lasting impact on their livelihoods and healthcare status for some time to come. The pool of research continues to grow, helping us to understand the breadth of this Public health Emergency (PHE) and its implications.

Many who have experienced COVID-19 firsthand continue to deal with health effect and are often referred to as long haulers. For caregivers in Long Term Care, these individuals present a unique challenge not only from the caregiving perspective but also on the health literacy front.

Hindsight is 20 20 and we are sure gaining perspective as we look back over the last year. Long term care has been under a microscope and there will be systemic changes that must occur relative to the insights gained. One that has been highlighted in the FY 2022 SNF PPS proposed rule and has been evident throughout the pandemic is the issue of health equity and in particular health literacy.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions. Health literacy challenges impact older adults more than other age groups. On average, adults age 65 and older have lower health literacy than adults under the age of 65. In a recent article titled, “How to Bridge the Health Literacy Gap”, the authors noted, “Large national studies show that about one third of American adults have limited health literacy. However, among many population subgroups, including older adults and some racial/ethnic minorities, the rate exceeds 50 percent, meaning that most individuals in those groups have limited health literacy.” (See data table below

Health literacy has become a focal point not only because the data shows that it is an issue that faces the population of individuals we care for every day in LTC, but within the framework of the recent emphasis on health equity, it rises to the surface as one of the important factors that drives positive or negative health outcomes. In the quality driven, resource stressed healthcare environment we find ourselves in, health literacy must become a priority.

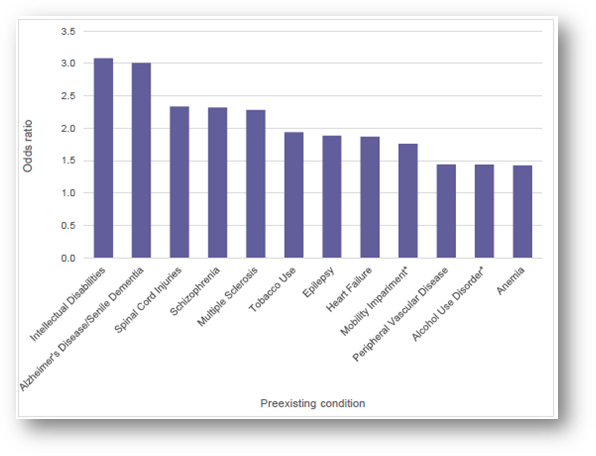

Consider the current PHE. COVID-19 has exposed the vulnerability of certain population segments to poorer outcomes based on preexisting conditions, age, and ethnicity. In a recent white paper by FAIR Health, consideration was given to the data in the table below which quantifies the top preexisting conditions associated with death of COVID-19 patients 30 days or more after contracting the disease. Consider the list of preexisting condition in the table below and ask yourself how many residents you have had in your buildings with these in their diagnosis list.

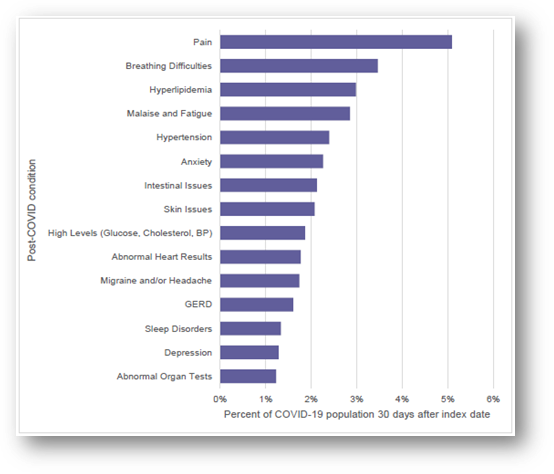

Consider also, from the same white paper, the statistics related to what are considered long haul or post covid conditions in the table below. Notice again, from this list, the familiar tone of the chronic conditions heard often in our patient populations. Given this data and the data related to preexisting conditions, age, and ethnicity, it is clear that as providers, we have our work cut out for us.

In a recent article published in the BMJ Open, an online, open access journal, dedicated to publishing medical research from all disciplines and therapeutic areas, researchers concluded that, “Compared with the general population, people with long-term conditions report more difficulties in understanding health information and engaging with healthcare providers. These two dimensions are critical to the provision of patient-centred healthcare and for optimizing health outcomes. More effort should be made to respond to the health literacy needs among individuals with long-term conditions, multiple comorbidities and low education levels, to improve health outcomes and to reduce social inequality in health.”

Knowing these things, we must act. Engaging the challenges of health literacy is not an optional activity, in fact, from the regulatory environment already in place it is a mandate. Here are some examples of CMS’ expectations from Appendix PP of the State Operation Manual.

- To cite deficient practice at F867, the surveyor’s investigation must generally show that the facility failed to: • Identify quality deficiencies; and • Develop and implement action plans to correct identified quality deficiencies.

From the investigative protocols for this tag, examples of Severity Level 3 Non-compliance Actual Harm that is Not Immediate Jeopardy include, but are not limited to:

Evidence showing the facility had repeat deficiencies for the past two surveys related to their failure to ensure residents’ post discharge needs were care planned and met upon discharge. During the current survey it was determined that a resident was discharged with no education about how to manage his new onset diabetes, resulting in his rehospitalization. The QAA review showed the QAA committee was not aware of the issue, and was not monitoring its practices around discharge.

- F883 Influenza and pneumococcal immunizations, the facility must develop policies and procedures to ensure that- (i) Before offering the influenza immunization, each resident or the resident’s representative receives education regarding the benefits and potential side effects of the immunization.

- Regarding the Provision of Immunizations, in order for a resident to exercise his or her right to make informed choices, it is important for the facility to provide the resident or resident representative with education regarding the benefits and potential side effects of immunizations.

- Baseline Care Plans: The facility must develop and implement a baseline care plan for each resident that includes the instructions needed to provide effective and person-centered care of the resident that meet professional standards of quality care. The baseline care plan must— Be developed within 48 hours of a resident’s admission. The facility must provide the resident and their representative with a summary of the baseline care plan that includes but is not limited to: The initial goals of the resident. A summary of the resident’s medications and dietary instructions. Any services and treatments to be administered by the facility and personnel acting on behalf of the facility. Any updated information based on the details of the comprehensive care plan, as necessary.

- Comprehensive Care Plans: The facility must develop and implement a comprehensive person-centered care plan for each resident, consistent with the resident rights that include measurable objectives and timeframes to meet a resident’s medical, nursing, and mental and psychosocial needs that are identified in the comprehensive assessment. The comprehensive care plan must describe the following — In consultation with the resident and the resident’s representative(s)— A. The resident’s goals for admission and desired outcomes. B. The resident’s preference and potential for future discharge. Facilities must document whether the resident’s desire to return to the community was assessed and any referrals to local contact agencies and/or other appropriate entities, for this purpose. C. Discharge plans in the comprehensive care plan, as appropriate…

These requirements are also fleshed out in the Survey Critical Element pathways. These are the pathways that surveyors use when conducting surveys in LTC communities. These pathways contain specific guidelines for conducting the survey related to specific issues as well as interview question that surveyors are instructed to ask residents and staff.

- From the General Critical Element Pathway Resident, Resident Representative, or Family Interview:

- How did the facility involve you in the development of the care plan and goals?

- What are your goals for care? Do you think the facility is meeting them? If not, why do you think that is?

- For newly admitted residents, did you receive a summary of your (or the resident’s) baseline care plan? Did you understand it?

- From the Record Review:

- Is there evidence of resident or resident representative participation in developing resident-specific, measurable objectives, and interventions? If not, is there an explanation as to why the resident or representative did not participate?

- Is there evidence that the resident has refused any care or services that would otherwise be required, but are not provided due to the resident’s exercise of rights, including the right to refuse treatment? If so, does the care plan reflect this refusal, and how has the facility addressed this refusal?

- From the Discharge Critical Element Pathway Observations:

- How are staff providing education regarding care and treatments in the care plan?

- How does the resident perform tasks or demonstrate understanding after staff provides education?

- From the Resident, Resident Representative, or Family Interview:

- What was your involvement in the development of your discharge plan?

- What has the facility talked to you about regarding post-discharge care?

- What discharge instructions (e.g., medications, rehab, durable medical equipment needs, labs, contact info for home health, wound treatments) has the facility discussed with you? Were you given a copy of the discharge instructions? If applicable, did the facility have you demonstrate how to perform a specific procedure so that you can do it at home?

Remember Section Q of the current MDS? This section requires particular attention to be paid to discharge planning when a resident has requested to return to the community.

Don’t forget the delayed implementation of the MDS 3.0 item set v1.18.0. Set to be released two fiscal years after the PHE there are at least two items in this assessment that relate directly to Health Literacy.

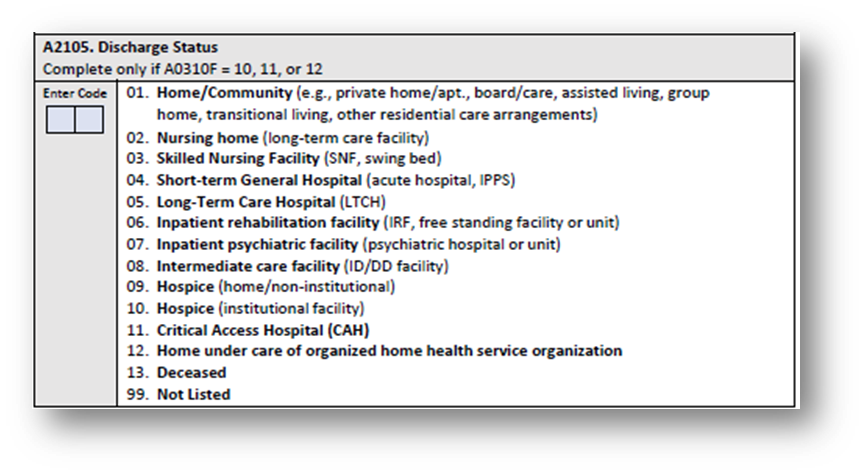

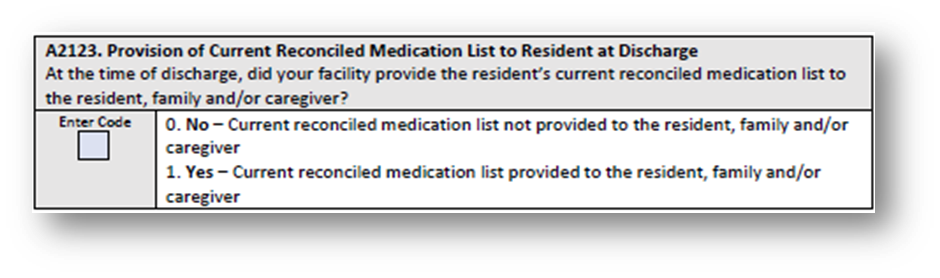

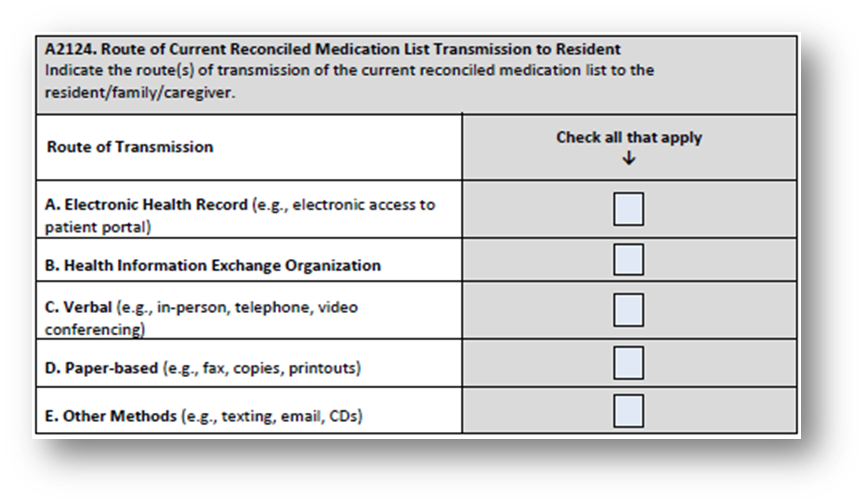

The first is a new QRP measure Transfer of Health Information to Patient. This measure, assesses for and reports on the timely transfer of health information, specifically transfer of a medication list. This measure evaluates for the transfer of information when a patient/resident is discharged from their current setting of PAC to a private home/apartment, board and care home, assisted living, group home, transitional living, or home under the care of an organized home health service organization or hospice. It will require new MDS items, see below.

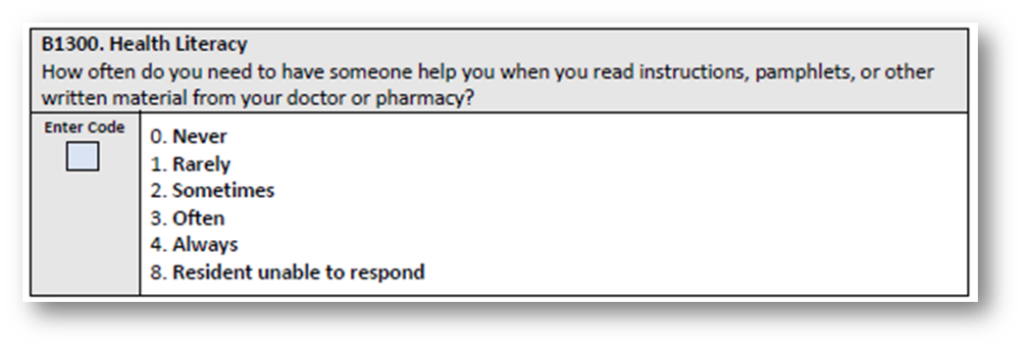

Second, The IMPACT Act requires CMS to develop, implement, and maintain standardized patient assessment data elements (SPADEs) for PAC settings. CMS has identified data elements for cross-setting standardization of assessment for seven social determinants of health (SDOH). The data elements are as follows: 1. Race, 2. Ethnicity, 3. Preferred Language, 4. Interpreter Services, 5. Health Literacy, 6. Transportation, 7. Social Isolation. Each of these will require new MDS items to accomplish measurement. Here are the data elements for Health Literacy.

Practically, then, we as providers must incorporate meaningful health literacy processes into our daily interactions with our residents. It is the IDT’s responsibility to ensure that health literacy issues are identified and addressed.

In the article “How to Bridge the Health Literacy Gap”, the authors noted, “Because limited health literacy is so common, we should assume that all patients need and want easy-to-understand explanations about their medical problems and what they need to do about those problems.” They suggest five strategies for communicating with all patients, not just the ones you suspect have limited health literacy. I have adapted these here for consideration with the LTC population.

1. Explain things without using medical terms. After you’ve been working with a patient for a while and listening to the terms they use when discussing their medical problems, you will be able to better match your communication to their level of understanding. But for starters, err on the side of simpler, rather than more complicated, explanations.

2. Focus on only two or three key messages. In any individual encounter, people tend to retain only two or three key messages. Pick the things your patients most need to know and emphasize those, rather than telling patients everything there is to know about their problem. If they want to know more they can ask, and patients with chronic problems will learn more over time. Not overloading them with information helps ensure that they will remember most of your messages and know what was most important.

3. Speak more slowly. Speaking at a slower pace will make you easier to understand when talking about topics that might be unfamiliar to the listener. If you are worried that your patient encounters will take too long if you speak slowly, consider that limiting your discussion with patients only to the key messages, as discussed above, will reduce visit length.

4. Use teach-back. Have your patients repeat your instructions back to you in their own words so that you can be sure that you explained it to them in a way that was understandable.

5. Use easy-to-understand written materials. Just like your spoken instructions, any written information provided to the patient should be easily understandable. Write down the key things your patient needs to do, whether it is preparing for a lab test, scheduling a future appointment with their doctor, or taking a new medication, and make sure it is free of medical jargon.

Finally, to bring this full circle, consider that the PDPM was created to undergird just such a responsibility. If you remember, when the PDPM was being implemented, CMS indicated that it was created to help providers make better care decisions.

- Consider that from CMS 100-2 Chapter 8, CMS expects providers to understand that teaching and training activities, which require skilled nursing or skilled rehabilitation personnel to teach a patient how to manage their treatment regimen, would constitute skilled services.

- The documentation must thoroughly describe all efforts that have been made to educate the patient/caregiver, and their responses to the training. The medical record should also describe the reason for the failure of any educational attempts, if applicable.

- The example that is offered is: A newly diagnosed diabetic patient is seen in order to learn to self-administer insulin injections, to prepare and follow a diabetic diet, and to observe foot-care precautions. Even though the patient voices understanding of the nutritional principles of his diabetic diet, he expresses dissatisfaction with his food choices and refuses to comply with the education he is receiving. This refusal continues, notwithstanding efforts to counsel the patient on the potentially adverse consequences of the refusal and to suggest alternative dietary choices that could help to avoid or alleviate those consequences. The patient’s response to the recommended treatment plan as well as to all educational attempts is documented in the medical record.

It is critical that we take on the responsibility that CMS Cleary expects regarding our place in the health literacy pathway that our patients are on. This is good patient care and demonstrates an good understanding of the disparities that exist when individuals are not literate with regard to their health.

The data clearly demonstrates that the population of patients that we typically see come through the doors of a LTC community are at much greater risk for poor outcomes relative to the place they reside in the health literacy spectrum. COVID-19 has only opened the disparity door wider and has given us a view we may not have had otherwise.

CMS’ triple aim of Better Care, Smarter Spending and Healthier People/Healthier Communities can be realized. One small step we can take is empowering those for whom we are charged to care with the tools they need to take charge of their health. That will be giant leap forward for us as providers and for the ones who will be healthier tomorrow because we take this responsibility seriously today.